Morocco: a trip report (part one)

I posted a trip report for Romania and then wrote about traveling in Norway, so I figured, why not write about Morocco?

I traveled with my cousin Caden and our friend Talia. Morocco is around the same size as California and we only saw a small slice of it. Here are my assorted notes on that small slice.

I have to split this into two parts — otherwise, it’s too long for Substack to handle. Part One will cover Marrakech, Amssakrou, Imlil, Asni, Moulay Brahim, and Tabounte. Part Two will include M’Hamid El Ghizlane, the Sahara, the villages of the Drâa Valley, Essaouira, and some miscellaneous observations about Morocco.

Marrakech

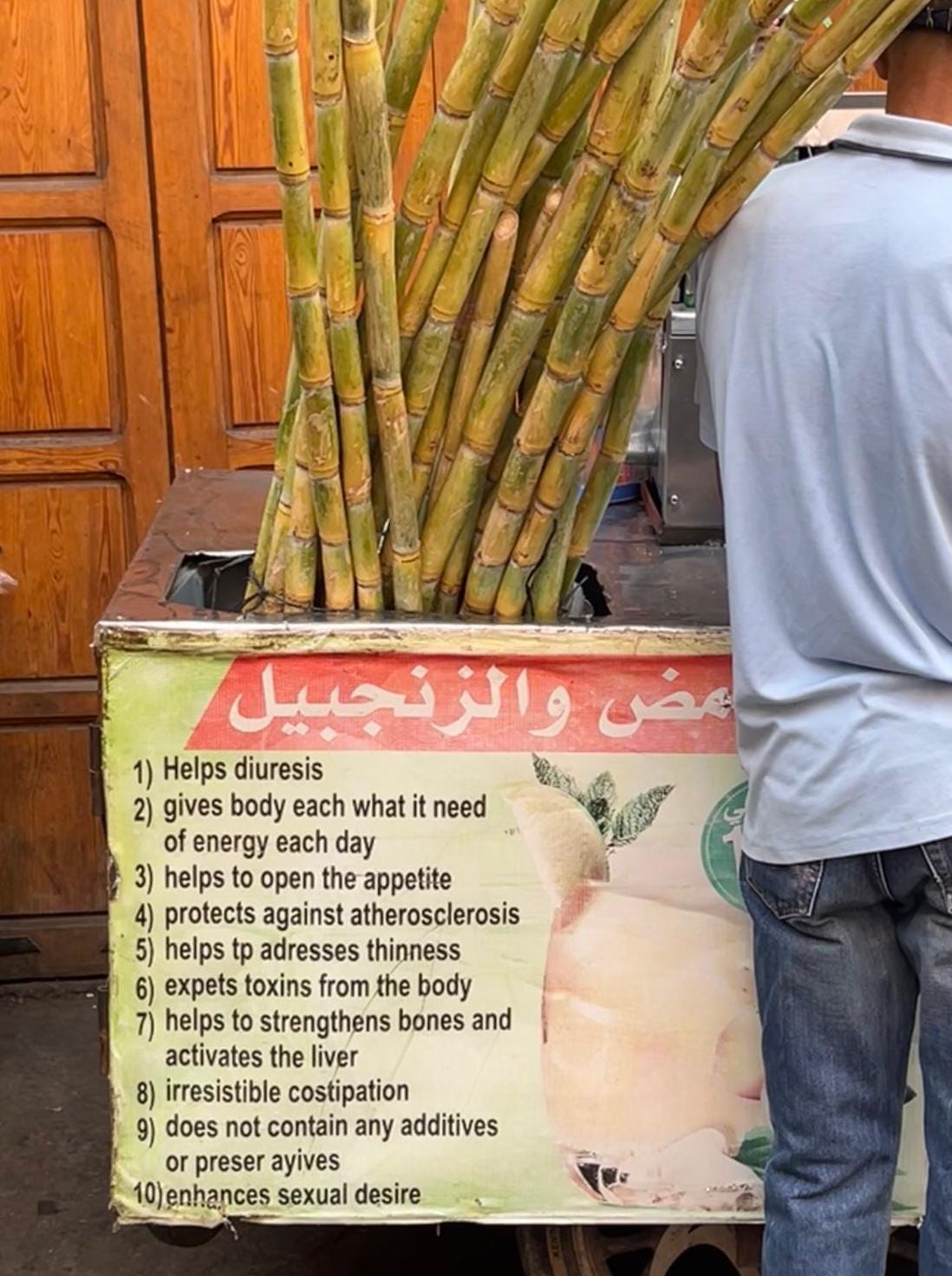

Marrakech is an absolute hole, and I’m going to cover much more interesting places in this writeup. Thus, the above is the only Marrakech photo I’m posting: the supposed benefits of drinking sugarcane juice.

The proprietor of our hostel said to abide by one rule in Marrakech: if someone starts a conversation with you, walk away. At first, I found that advice cynical, but it turned out to be wise.

The most common scam is as follows: while you’re traversing the old city’s spiderweb of alleys and semi-subterranean passageways, trying to find a route from point A to point B, a man will approach you and tell you that this road is closed, but out of the goodness of his heart, he will show you the right way to go. Then he will lead you somewhere secluded and empty your wallet. Since we had been warned, we simply walked past these men without acknowledging them.

Marrakech is nothing if not atmospheric. In our first ten minutes in Marrakech, I saw a cage full of chickens with people eating off the top of the cage as if it were a table; a man splayed out in a wheelbarrow, half-buried in pomegranates; a boy no older than nine years old riding a motorcycle; many cats, most of which were alive; and a group of men standing in the middle of the street, simultaneously selling grapes and welding.

The novelty wears thin quickly. Marrakech is an Orientalist hallucination of the Arab world, replete with snake charmers and herbalists and opportunities for holidaymakers to LARP Lawrence of Arabia. We got out as fast as we could.

Amssakrou

We threw a dart at booking dot com, and we landed on a guesthouse in a random village in the High Atlas called Amssakrou. The proprietor of our hostel in Marrakech had never heard of Amssakrou and seemed befuddled as to why we wanted to go there.

The owner of the guesthouse in Amssakrou initially rejected our booking on the grounds that we were two men and an unmarried woman sharing a room. Apparently, that is illegal for Moroccan citizens.

A baffling, protracted negotiation followed, in which Google Translate misinterpreted the Darija1 word for ‘marriage certificate’ as ‘carton of milk’. With the help of a bilingual Moroccan, all parties finally understood the issue and all was forgiven.

The owner, Abdo, met us in the nearest town and drove us to Amssakrou. Abdo spoke about as much Darija as I did (200+/- words) — thankfully, he spoke some French. His first language was Shilha, one of Morocco’s Amazigh2 languages. We had a blast driving up the winding gravel road to Amssakrou as Abdo taught me Shilha by pointing to things (goats, donkeys, children, mosques) and saying the Shilha word, then laughing when I mispronounced it.

Amssakrou was my favorite place in Morocco. There wasn’t much to do there except wander, chat, and drink tea. Exactly my kind of travel.

Abdo dispatched two local girls, Fatiha and Madiha, to show us around, as they had seen us around the village and were curious about us. They led us on a hike down to the river at the heart of the valley. It was at this point that I fully comprehended the limitations of my Darija skills.

“What’s this called?” I asked, pointing to the river.

“Water?” Madiha said.

“Right,” I said, “but what’s… its name?”

“It’s a river,” Madiha said. Then she looked at Fatiha as if to say ‘are Americans stupid?’ and they both giggled.

On our last day, I asked Abdo: “How much would a house in Amssakrou cost?”

He said they don’t really buy and sell houses in Amssakrou; they just build and demolish them as needed. He said that if I wanted to move to Amssakrou, he would employ me at his shop. The only stipulation was that I would have to learn Shilha and convert to Islam.

There’s a mosque at the center of each village in the High Atlas, and locals can spot and identify each village from a distance by locating its corresponding minaret. The mosques aren’t just used for the call to prayer; during our time in Amssakrou, there was an announcement from the mosque loudspeaker that the men would be gathering to harvest the walnuts at nine tomorrow morning, and if they did not want to participate in the harvest, they would have to pay a fine of 200 dirham. ($54.46)

Imlil, Asni, and Moulay Brahim

Imlil is a scenic little town at the foot of Mount Toubkal, the highest peak in Morocco and the Arab world. Imlil was made for tourists, like Cancún, and feels like an outpost of Marrakech. (Lots of guys trying to sell you a bracelet or a rug; lots of Europeans with questionable haircuts staring into their phones and ‘finding themselves’.)

Near Imlil is the town of Asni. Asni was about 50% destroyed in the 2023 earthquake. We found a cafe in Asni full of locals smoking and playing billiards. The cafe owner, Youssef, was gobsmacked to see foreigners and even more gobsmacked that I spoke some Darija. He brought us tea and charged us almost nothing.

Youssef and I talked about Moroccan politics and American politics and the Russian invasion of Ukraine. He said that he ended up in Asni because he was displaced from his home village, Moulay Brahim, after the 2023 Al Haouz earthquake.

Youssef said: “Honestly, that day is hard to forget. It was really tough — so many people I know lost their homes. Thank God, nothing happened to me and my children. But my daughter is still scared at night even now because of the trauma of the earthquake.” He noted that 2,976 people died in 9/11, and 2,960 people died in the 2023 earthquake.

Youssef said, if we wanted to understand Morocco, we should see places like Moulay Brahim, where the government was supposed to be rebuilding but had entirely “disappeared” the funds.

So we hopped on a van3 to Moulay Brahim, which was standing room only by the time we arrived. The driver tied our backpacks to the roof of the van with rope. The van stopped multiple times so older women with ginormous bags on their backs could sell water bottles and pass bundles of some kind of grain through the windows.

Moulay Brahim was one of the most disheartening places I’ve been, but I’m glad I saw it. It’s fifteen kilometers from one of North Africa’s hottest tourist destinations, but most tourists will never see this side of Morocco. Most of the locals now live in makeshift tents. The government has apparently made little progress in reconstruction, and the aid distribution process is byzantine and ineffective. The desperation is palpable.

Nearby is a mega resort that Richard Branson built last year, surrounded by high walls topped with barbed wire.

Tabounte

Around 270+/- kilometers separate the High Atlas from the Sahara, so we broke up the bus journey with two nights in Tabounte. We had intended to book a place in Ouarzazate, the big city next door, but I messed up and we wound up in Tabounte. I couldn’t be more grateful for this snafu, as I really enjoyed Tabounte.

Tabounte is composed of stark, boxy houses separated by alleys wide enough for three Americans to walk single file. Of everywhere we went in Morocco, Tabounte was the place Moroccans were most surprised to see foreigners.

Tabounte also had the most cheerful street life of everywhere we went in Morocco. At all hours, there were families out and kids playing soccer and old people having chats on the sidewalk.

Both nights in Tabounte, we had a great $1/person dinner at Snack Nour. While we ate, two little boys stood and stared at us for a while; when I greeted them in Darija, they screamed and ran away.

While I was in line to check out at the corner store, the burqa-clad grandma in front of me asked “France?” I said “America” and she said “America! Wonderful!” (in Darija) and gestured for me to go in front of her in line. I said no, no, go ahead. We did the song and dance until it was her turn to check out.

I enjoyed Tabounte. What can I say? I like being an oddity.

This concludes part one; you can find part two here.

Moroccan Arabic.

Amazigh is the proper word for Berber. Berber is an exonym that shares an etymology with the word ‘barbarian’. Most Amazigh/Berber folks whom I asked didn’t seem to care which word I used, but in the interest of not calling anyone a barbarian, I’ll use Amazigh in this post.

I have no idea what this is called in English or Arabic, but in Ukraine and the post-Soviet world in general, it’s called a marshrutka.

This was excellent!

Taking the advice of the proprietor of the hostel is a necessity, an urgent necessity. As a Moroccan guy, I do the same when attending places like bus stations, markets, and so on and so forth. Tourists learn just to ignore the approacher, especially if he is an intruder, while I add this sentence when retreating: 'Sir tkawad rah mkawda aliya' Hahaha I am joking; I just make intense eye contact and move on. For the saying, it literally means, 'Go the hell away; I am broke now.' Anyway, long story short, I frequently thumb through Substack, and sometimes I search for stuff relevant to my country. I ended up enjoying this post. It is so reminiscent to me because I was growing up in the region of Draa Taffilat, in a rural area exactly the same way as the two little girls. Back then there was no social media. Unlike the shyness of Fatiha and Madiha, we were meddlesome pests haha, and the tourists were generous, mostly old couples with large camping vehicles. When all is said and done, one wonders what will be left of the memory of Fatiha and Madiha when they reach 25.